Cold Case: Ragged Island double murder still unsolved after 35 years

Published 1:40 pm Tuesday, September 27, 2022

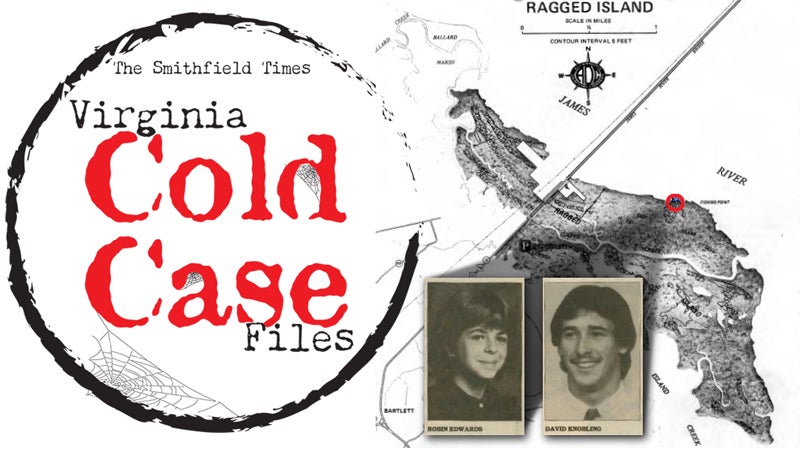

- Among the files included in the Virginia State Police cold case database on the Ragged Island murders is this map showing approximately where David Knobling's and Robin Edwards' bodies were found, and photos of the two victims.

Editor’s note: A new state law requires Virginia State Police to maintain a publicly accessible online database of unsolved homicides, unidentified bodies and missing-person cases. Three of the database’s 60 cases are from Isle of Wight County. This is the first in a three-part series. The other installments will be published in late October and late November.

It’s been 35 years since an Isle of Wight County sheriff’s deputy on nighttime patrol found 20-year-old David Knobling’s pickup truck parked at the Ragged Island wildlife refuge – doors closed but unlocked, driver’s side window down and its radio left playing with no one inside.

Two days later, on Sept. 23, 1987, a beachcomber discovered the bodies of Knobling and 14-year-old Robin Edwards lying on Ragged Island’s shoreline roughly a mile from the James River Bridge. Both had been shot in the back of the head at close range.

The double murder remains unsolved, one of several decades-old crimes now listed in an online Virginia State Police database of cold cases that debuted in June.

Janette Edwards Santiago, Robin’s older sister, remembers her younger sibling as “free-spirited” and “hard-headed.”

“She was never afraid of anything … always believed nothing was going to happen to her,” Santiago said.

The then-19-year-old had been living on her own when she received a phone call from her parents Saturday night, Sept. 19, 1987, asking whether she’d seen Robin that evening. She answered, “no.”

“I didn’t think a whole lot of it at the time because she had run away a couple months previously and was gone for two weeks,” Santiago said.

The sisters “weren’t really speaking” at the time, Santiago recalls, and hadn’t been since the day she’d told on Robin for having ridden her bicycle from their parents’ house in Newport News almost all the way to the Coleman Memorial Bridge in York County.

Santiago had attended elementary school with Knobling, who’d lived in Hampton, but hadn’t seen him since. Robin, she recalls, had arranged a date on Sept. 19 with Knobling’s cousin, Jason.

As Santiago recalls from her mother’s account of events, Jason, David and David’s brother, Michael, had shown up at the Edwards home in David’s truck the evening of Sept. 19 to take Robin to a movie that ended up being sold out. The four went to an arcade instead, dropping Robin back at her parents’ house around 10 p.m.

Michael, who now lives in Newport News, confirmed Santiago’s version of events. He and David are technically half-brothers. David’s stepfather, Karl, had divorced David’s birth mother and remarried to Kathy Knobling by 1987. David’s birth father “wasn’t ever really in David’s life,” said Michael, who provided no additional comments for this story.

Once home, Robin put her younger sister, Pam, to bed, but at some point went back out later that night with David.

Why the two ended up traveling all the way across the James River Bridge to Ragged Island remains a mystery.

“David’s girlfriend was pregnant,” Santiago said, recalling her mother’s speculation that Robin “was a problem-solver” and may have been trying to help David figure out what to do.

Santiago then hinted at the possibility of some sort of love triangle, noting David “was a good-looking boy” and Robin “was a good-looking girl.”

Ragged Island, according to letters to the editor published in The Smithfield Times at the time, had a reputation as a secluded “lovers lane” where young couples would park their cars to be alone together.

Sept. 21-23, 1987

According to an Oct. 28, 1987, letter by then-Isle of Wight Sheriff B.F. Dixon, the deputy who’d found David’s truck early Monday, Sept. 21, had exited his patrol car at 3:33 a.m. and walked through the island looking for who might have left the vehicle – but found no one. He returned to his car at 4:10 a.m. to check the truck’s license plate and continued to wait at the scene in case anyone showed up.

At 5:24 a.m. the Sheriff’s Office made its first attempt to contact David’s family by phone, but received no answer. At 6:41 a.m. another call was made, also receiving no answer. At 7:40 a.m. “Mrs. Knobling answered” and told a dispatcher she “had no idea” where David was.

The deputy then walked through the island again, but still found no one. By 12:20 p.m. Newport News detectives and Karl, had arrived on the scene. Karl, according to Dixon’s letter, told detectives he “was sure something was wrong.”

Robin’s mother, Bonnie, was also called by police to identify items that had been left in David’s truck, Santiago recalled. She identified Robin’s tennis shoes and some of her clothes.

David and Robin were officially reported missing later that day.

During the next day and a half, Robin’s parents went to WAVY television station for an interview and pleaded for Robin to come home.

Santiago remembers Pam and their parents gathering around the TV the evening of Sept. 23, 1987, to watch the 5 p.m. news, hoping for an update on Robin.

During the broadcast, WAVY reported two bodies shot execution-style had just been found on the beach that morning at Ragged Island, identifying the victims as 20-year-old David Knobling of Hampton and 14-year-old Robin Edwards of Newport News.

“That’s how we found out my sister was gone,” Santiago said.

Misplaced evidence?

According to the Times’ Sept. 30, 1987, story on the shooting, Dixon told reporters on Sept. 28 that his office hadn’t yet received a ballistics report on the weapon used but believed it to be “larger than a .22” caliber. But beyond that, there had been no physical evidence to prove where the murders occurred.

There was, however, widespread speculation at the time that David and Robin had been shot on a boardwalk built across the Ragged Island marsh, their bodies then drifting to where they were found after being dumped into the James River.

“They had nothing to go on,” Santiago recalled. “Back then, DNA wasn’t a big thing.”

By this time, the number of agencies working the case had expanded to include the Virginia State Police and Hampton Police Department. The State Police would eventually take over the case.

Carrollton resident Andrew M. Casey, a retired Army military police supervisor, had written an Oct. 21, 1987, letter to the editor in the Times claiming “no one remembered to impound the truck and process it for evidence,” after David and Robin were reported missing, and that the vehicle had been “returned to the home of the male victim’s parent.” Casey, now 84, still lives in Carrollton and recalled writing the letter, but not exactly what he had written.

Dixon, whose Oct. 28 letter had been in response to Casey’s, disputed the allegation. In his letter, the former sheriff contended the truck had been “moved to Newport News where it was processed” by the Newport News Police Department’s forensics unit, and inquired whether Casey had “political reasons” for writing to the Times a month after the fact.

The double murder had occurred just over a month shy of a contested November 1987 election where voters would choose the next Isle of Wight County sheriff. Dixon had announced his pending retirement earlier that year, leaving his son and chief deputy, Drew Dixon, vying for the job against then-Smithfield Police Lt. Charlie Phelps and self-proclaimed “long shot” candidate Deputy E.L. “Duke” Dickerson.

Santiago’s recollection of the investigation, however, corroborates Casey’s allegation that the truck was returned to David’s parents prior to being dusted for fingerprints. Phelps, who ultimately won the 1987 sheriff’s election, also recalled that one of the police agencies investigating the case had gone back to collect additional evidence from the truck after it had been returned to the Knobling family.

Santiago recalls David’s stepmother, Kathy, contacting police after they’d finished dusting the truck for prints in her driveway to inform them she was holding the fingerprint film they’d dropped outside her home in the rain.

Asked about the allegedly misplaced fingerprint film, State Police spokeswoman Sgt. Michelle Anaya said the agency’s Bureau of Criminal Investigations “will not confirm any specifics about any evidence seized in an active investigation.”

According to Anaya, there are no agents still employed by the State Police who investigated the 1987 double murder, but “the latest forensic technology is being utilized to generate new leads.”

Maj. Joseph Willard, now chief deputy in Isle of Wight under Sheriff James Clarke Jr., confirmed to the Times he’d been the deputy to have initially discovered David’s truck at Ragged Island, but deferred further comments on the still-active case to the State Police.

“We turned over any information that we have acquired decades ago to the Virginia State Police and have not participated in any further investigative efforts,” said Deputy Alecia Paul, the Sheriff’s Office’s assistant public information officer.

The work of a serial killer?

According to the FBI’s Norfolk division website and past press releases, the Ragged Island cold case may be linked to three other unsolved double homicides with similarities from the 1980s known as the Colonial Parkway Murders.

The first double murder occurred in 1986. On Oct. 12 of that year, U.S. Park Service rangers found the bodies of 27-year-old Cathleen Thomas and 21-year-old Rebecca Dowski inside Thomas’ car in a wooded area near the York River off the Colonial Parkway, a highway that connects James City and York counties. Thomas, a recently discharged Navy lieutenant, and Dowski, a student at the College of William & Mary, had last been seen alive the evening of Oct. 9 in a computer lab on William & Mary’s campus. Both women’s “throats were slit from ear to ear,” according to Oct. 14, 1986, reporting by The Daily Press.

Roughly six months after David and Robin were found murdered, 20-year-old Richard “Keith” Call’s father found his son’s car abandoned at the York River overlook off Colonial Parkway the morning of April 10, 1988. According to the FBI, Call had been on a first date with 18-year-old Cassandra Hailey at a Christopher Newport University party in Newport News that had begun the night before and lasted through midnight. As with Robin, clothes belonging to Call and Hailey were found inside Keith’s car, but neither victim has ever been located.

The Suffolk News-Herald and Daily Press reported in 1988 that a former Gloucester County private detective facing deportation had claimed days after the disappearance of the two CNU students to be the FBI’s chief suspect in that case, and in the slayings of David and Robin, though the FBI and immigration officials denied his allegation.

The Daily Press had reported 32-year-old Ronald Little, originally of New Zealand, had job ties with Robin’s mother, and had sent a six-page letter filled with accusations to several newspapers and talk show hosts. FBI agents, according to the Suffolk story, did question Little and searched his car. Little was ultimately deported in August of that year.

Roughly a year and a half later, on Oct. 19, 1989, hunters found the bodies of 18-year-old Annamaria Phelps and 21-year-old Daniel Lauer on a logging road less than a mile from an Interstate 64 rest stop in New Kent County. According to reporting by The Farmville Herald, Annamaria and Lauer had left Amelia County on Sept. 4 heading for Virginia Beach, where she was set to marry Lauer’s brother, Clinton, on Sept. 25. They were last seen at the westbound rest stop around 1 p.m. on Sept. 5, though they should have been heading east. Later that day, the car was found parked at the rest stop’s truck acceleration on-ramp with no one inside.

Like with David’s truck, the vehicle’s key had been left in the ignition. Daniel’s clothes and Phelps’ purse had also been left inside.

A new sheriff in town

Charlie Phelps, who served as sheriff for 24 years until December 2011, inherited the Ragged Island double murder case upon taking office in January 1988, though by this time the State Police had taken over as the lead law enforcement agency.

“We cooperated with each other, we didn’t have any conflict on that, but … the State Police basically had recovered any type of evidence, which was very little,” Phelps told the Times in an interview at his home last week.

Three to four months after taking office, Phelps would uncover a new lead while working another case.

In April or May 1988, an Isle of Wight woman reported several firearms as having been taken from her home. Phelps came to suspect the woman’s son of the theft.

When the son was detained in Jacksonville, Florida, on Isle of Wight charges, Phelps and a State Police investigator flew there to question him.

“I don’t remember how it happened, but the Ragged Island situation came up,” Phelps said.

The son, Phelps recalls, had confessed to taking a gun from his mother’s home and selling it at a pawn shop in Mississippi but then began talking about a roommate who’d lived with him and his mother in Isle of Wight County named Samuel “Sammy” Rieder. According to Blaine Pardoe’s and Victoria Hester’s 2017 book, “A Special Kind of Evil: The Colonial Parkway Serial Killings,” 28-year-old Rieder had just gotten out of prison for forging a $60 check, and had called in one of the original tips the Sheriff’s Office had received when investigating David’s and Robin’s initial disappearance.

The son, Phelps recalls, told him that Rieder had taken an interest in the Ragged Island case and had made some comments about it. When Phelps returned to Virginia, he tracked down Rieder and questioned him.

“I kept getting different stories out of him about Ragged Island,” Phelps said.

As Phelps recalls, Rieder had initially claimed to have stopped at Ragged Island out of curiosity on Sept. 23, 1987, when David’s and Robin’s bodies were found, then later claimed to have seen Knobling’s truck parked at Ragged Island days earlier.

“At that point, I took him into an interview room at State Police headquarters in Norfolk and started questioning him about the inconsistencies in his statements,” Phelps said.

Rieder’s final version of events, Phelps recalls, was that he had taken money out of Knobling’s wallet, which had been left in the truck, but fled the scene when he heard a loud noise.

“I was getting information” that David “supposedly had a firearm in the truck,” Phelps said. Rieder “claimed, of course, … that he didn’t see any gun” and would not admit to having anything to do with David’s or Robin’s deaths.

Phelps gave Rieder a polygraph test, which proved inconclusive as to whether he was telling the truth.

Phelps’ theory is that David returned to the parking lot upon hearing someone rifling through his truck, surprising Rieder mid-theft, and that Rieder indeed shot David and Robin.

Robin, Phelps recalls, had been shot only once in the back of the head. But David, in addition to the execution-style gunshot wound, had also been shot in the back at an angle that suggested he had been leaning forward, “which would have been conducive with him running.”

“I firmly believe that my suspect was the one who killed those two people,” Phelps said.

But with uncertainty as to whether a wallet had been recovered from the truck or whether David had indeed kept a gun in the vehicle, Phelps held off charging Rieder with the theft.

According to an Aug. 1, 1990 Smithfield Times story, another theory police were pursuing at the time was that the murderer was “an authority figure,” due to there being little evidence of a struggle aside from David being shot twice. In the same story, Kathy Knobling told the Times it was her belief that the murderer had been posing as a police officer or was “a cop gone bad.”

There was also nothing to connect Rieder to any of the other Colonial Parkway murders, Phelps noted, other than that once Rieder died, “there were no more Colonial Parkway murders after his death.”

According to Phelps, Rieder died sometime after the bodies of Annamaria and Daniel were found in 1989 — allegedly by choking himself while masturbating. The “Special Kind of Evil” book, however, asserts that Phelps had been told this information by someone else. The Smithfield Times has been unable to find an obituary or other record to confirm if and when Rieder died.

Santiago receives updates from the State Police every six months to a year, but to date she’s learned of no new leads. All she can do, as she’s done for the past 35 years, is wait and hope someday, somehow, she’ll have closure.