An important new James Monroe biography

Published 4:22 pm Tuesday, August 4, 2020

By Wilford Kale

Of all the founding fathers of this nation, probably the least known and least understood is James Monroe, the fourth in the early line of Virginia-born United States presidents behind Washington, Jefferson and Madison.

When one thinks of George Washington, it’s the father of his country; Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, and James Madison, architect of the Bill of Rights.

But what of James Monroe, the nation’s fifth president, 1817-1825?

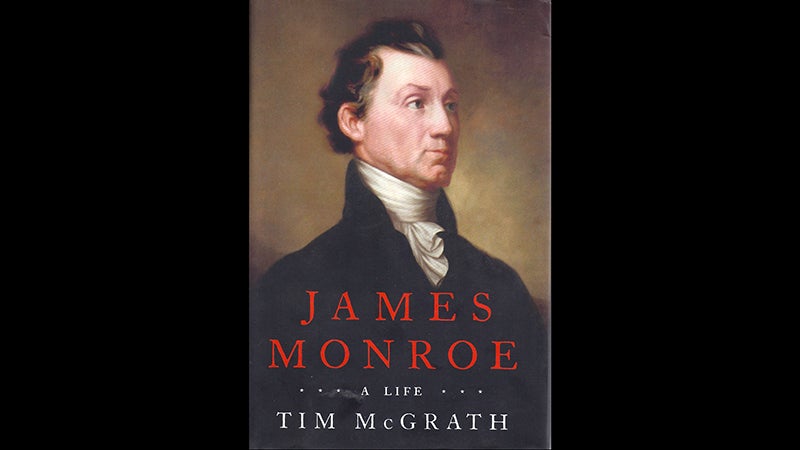

Previously, the preeminent biography of Monroe was written in 1971, nearly 50 years ago, by Harry Ammon, then professor of history at Southern Illinois University, and published by McGraw-Hill. Author Tim McGrath has created a new dynamic and revealing biography, “James Monroe: A Life” (Dutton 752 pgs., $40) which fills the void and raises the biographical bar.

Reading McGrath, it is easy to understand the extraordinary life of the “soldier, senator, cabinet member, diplomat and the last founding father president, soldier. It was Monroe who transformed the burgeoning nation into a powerful republic. McGrath’s clear and concise prose easily paints the various pictures of Monroe’s life.

McGrath gives Monroe’s education at the College of William & Mary a bit of a short shrift. Monroe studied at the college from 1774 to 1776 when he left, along with his roommate, to join the local militia and fight in the American Revolution. While those military events are recounted, McGrath overlooks the fact that Monroe returned to the college as a student in October 1779.

Monroe’s autobiography, written in third person, states that “Mr. Monroe immediately re-entered the college, [and] resumed his study of general science.“ About this time, McGrath writes about Monroe’s decision to begin law studies with Governor Jefferson.

Omitted is the fact that W&M began a law school in December 1779 under the tutelage of eminent lawyer George Wythe. Monroe’s decision was either to remain in Williamsburg at the college and study with Wythe or move to Richmond in April 1780 and study with Jefferson. Monroe’s uncle urged Monroe that if Jefferson “wishes or shows a desire that you go with him. I would gratify him.” Monroe did and his second W&M tenure ended.

Regarding Monroe’s military experience, McGrath is spot on. His research has opened new aspects of Monroe’s Revolutionary War challenges that included crossing the Delaware with Washington, the battle of Trenton, where Monroe was almost killed, Valley Forge and several other major battles. In 1779, however, Monroe wanted a field command that was not available and was the reason he returned to his W&M studies.

Later in 1793, Monroe decided to purchase Highland, a large homesite near his friend Jefferson’s home, Monticello. William and Mary received Monroe’s plantation in the mid-1970s in a bequest from philanthropist Jay W. Johns and has developed it into a wide-ranging interpretive historic site presenting not only Monroe’s more rural activities, but also the life of the enslaved persons who lived there and worked for him.

Former W&M president W. Taylor Reveley III, about 2014, established a college-wide commission designed to “push forward” Highland (known for more than 100 years as Ash Lawn) and to get the historic site “recognized anew.”

“All this was part of my larger effort to get James Monroe brought back into our national consciousness and, in the process, make clear his ties to William & Mary [that] tend to be ignored,” Reveley wrote in a recent email. McGrath, in fact, mentions Highland numerous times in his narrative.

The creation of the important government policy — the Monroe Doctrine — is thoroughly explained and McGrath praises and elaborates on Monroe two diplomatic trips to France, first in the midst of the French Revolution and second in 1803 as he was able to facilitate the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase.

This book is valuable, because it treats both the public and private Monroe.

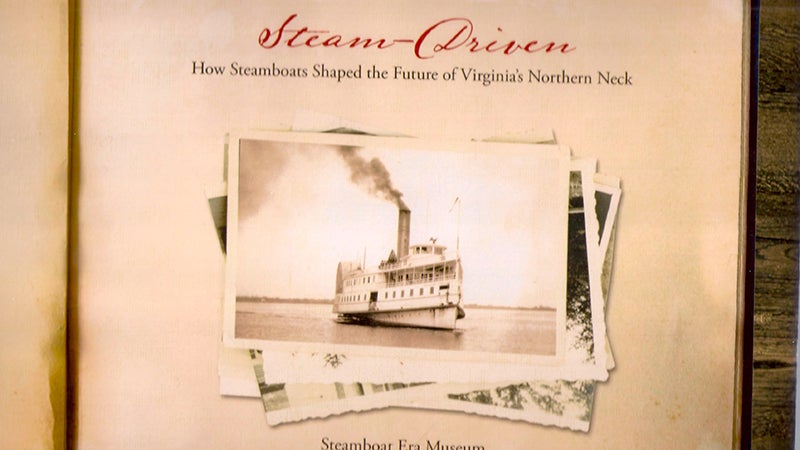

Steamboats enliven waters of the Chesapeake

From the mid-19th century through the first quarter of the 20th century, steamboats churned the waters of the Chesapeake Bay from Baltimore and Washington to Tidewater Virginia.

Shelly Ford’s delightful narrative brings that age to life in “Steam-Driven: How Steamboats Shaped the Future of Virginia’s Northern Neck” (Steamboat Era Museum, 88 pgs., $34.99). “To say that steamers wrote Northern Neck history is no understatement. In a region defined by its waterways, steamboats replaced an isolated existence with an era of growth and prosperity,” the introduction says.

The design, by Barbara Brecher, is first-rate and arranged in a kind of scrapbook format.

Many of the boats are examined. For example, in 1848 the Steamboat Pauxent offered “grand excursions” on the bay with dinner and music, that was in addition to regular service between Fredericksburg and Baltimore, Ford explains.

The coming of the Civil War brought steamboats into action ferrying men and supplies up and down the bay and into the inter-military workings of the James River. After the war, the regular steamer lines were re-established with passengers and goods now the cargo.

Eventually, the steamboat lines were owned by railroad companies. Another steamboat, Potomac, was severely damaged in a February accident, but its pilothouse was saved. A large portion of the book relates the preservation and restoration of the important pilothouse that now is the focal point of the Steamboat Era Museum in Irvington.

Wilford Kale, of Williamsburg, is a retired journalist and communications professional. His email address is kalehouse@aol.com.