Dante Wright, born into poverty, opens law firm with longtime mentor

Published 9:30 am Friday, February 2, 2024

- Retired Judge Gammiel Poindexter, left, with her adoptive grandson-turned-law partner, Dante Wright (Photo courtesy of Dante Wright)

A chance encounter with a local trailblazer started Dante Wright on his journey from poverty to the legal profession.

When one of 4-year-old Dante’s older brothers took his bicycle from him, Dante ran after him into the street just as General District Court Judge Gammiel Poindexter was driving home from work.

Poindexter, then two years into her tenure as the first female Black judge appointed to Virginia’s Sixth Judicial Circuit, had commuted past the boys’ Surry County house hundreds of times before stopping her car that day in 1997 to talk to Wright and walk him home.

Wright, now 30 and himself a practicing lawyer, describes his 26-year relationship with Poindexter as having now come “full circle.” She’s become his mentor, adoptive grandmother and now partner at the newly opened Poindexter & Wright law firm, which has offices in Surry and Smithfield.

Wright was born the youngest of seven children to parents who never finished high school. The year Poindexter came into his life, he’d been living with his mother and five siblings. His father was largely absent and his oldest brother, Curtis, had by that time moved away to live on his own.

All six of Dante’s siblings have had run-ins with the criminal justice system over the years. When Dante was 12, Curtis was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for double homicide.

Dante credits Poindexter with setting his life on a different path.

Poindexter, 79, remembers her first meeting with the family well.

“I went in the house to tell their mother that I had seen them on the road and we started talking,” Poindexter said. “She gave me a telephone number.”

Not long after, Poindexter began taking the children to the skating rink. Poindexter’s late husband, Gerald, even purchased a large van to transport the children to and from Chippokes State Park and other local attractions.

“I just enjoyed the company so much,” Gammiel said.

“Life was beautiful,” Dante recalled, but a year later, Child Protective Services would order the children removed from their birth mother’s custody and separated. Some went to group homes. Wright went to live with his paternal grandmother.

“She was a beautiful, very sweet lady” who “would play Pokemon cards with me,” Dante recalls. But by age 7, he was again forced to move, this time to live with his cousin, Paula, in a low-income housing complex. By age 9, he’d moved again to a trailer park in Newport News roughly an hour’s drive from his former home.

“I was fed, I had clothes” and “didn’t think that we were extremely poor,” Dante recalls. “We just didn’t have money.”

When Dante turned 11, the Poindexters gained temporary custody of him but the arrangement didn’t last and he was eventually sent to live with his biological father at an apartment in Smithfield. By age 15, when Gammiel and Gerald regained custody of Dante, he’d attended five different schools.

“When I was in 10th grade, Judge Poindexter caught wind of how difficult my living arrangement had become and she and her husband, the late Gerald Poindexter, offered me the opportunity to move in with them and finish out my high school career in Surry, Virginia,” Dante said. “I was elated and took them up on their offer. Finally, after 10 years of chaos, I had stability in my home life.”

Wright graduated Surry County High School with honors in 2011 and was awarded a scholarship to attend Virginia State University. Though there was never a formal adoption, Wright came to regard the Poindexters as his grandparents. They even listed him as their grandson in the graduation announcement published in The Smithfield Times that year.

Four years later, during his senior year at VSU, “I began asking myself what my next step would be,” Dante said. “To be quite frank, I was further in life than I ever expected to be. My parents didn’t finish high school, let alone considered ever graduating from college. Yet here I was, 21 years old, and on the cusp of accomplishing something I thought was impossible for someone of my background.”

Going to law school “seemed absurd,” Wright said. “When I lived with my mother, we had no money and had to accept government benefits. Was I the type of person that belonged in someone’s school of law? I certainly didn’t think so, but the Poindexters convinced me that I did.”

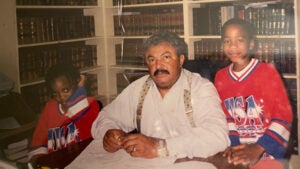

A young Dante Wright and his older brother, Leon, visit with the late Gerald Poindexter. (Photo courtesy of Dante Wright)

‘Those few decisive moments’

In 2016, his second year of law school at North Carolina Central University, he reconnected with Curtis.

“He began to call me from prison regularly,” Dante said. “Amazingly, he came across as well-read and well-spoken. While serving out his sentence, he committed himself to reading, taking courses, and learning more about God. I often wondered how someone who appeared to be so level-headed could find himself involved in a crime such as double homicide. I even wondered whether he was simply unlucky to be born the first of seven, and if my luck was rooted in being born last.”

In 2018, he received his juris doctorate with honors from North Carolina Central and, on his first attempt, passed the Washington, D.C. bar exam. That same year, just ahead of his graduation date, he got another call from Curtis, this time asking for an in-person visit.

“At this point, it’d been 17 or 18 years since I’d seen my brother,” Dante said. “He wasn’t sure how much longer he’d survive in Red Onion.”

Dante honored his brother’s request and made the seven-hour drive with his mother and sister from Surry to Red Onion, a supermax state prison located just outside the town of Pound in Wise County near the Virginia-Kentucky border.

“It was a very emotional experience, but one that I took a lot from,” Dante said. “What it showed me is that we are not so different from one another and it’s what we do with those few decisive moments in life that defines who we become.”

Dante would face his own decisive moment two years later.

The D.C. bar exam he’d passed qualified him to practice law in multiple states, but not Virginia. When the New Jersey law firm employing him went virtual in 2020 during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dante returned to Surry and, after months of studying, passed the Virginia bar exam on his first try.

Not long after, Gammiel got wind of an opening for an assistant commonwealth’s attorney in Sussex County, one of five jurisdictions that comprises the Sixth Judicial Circuit where she’d served as a judge until her 2007 retirement. Dante, who by that time had his heart set on opening a law firm with his longtime mentor, wanted no part of the job.

“I was completely against it,” Dante recalls.

But Gammiel was insistent. Becoming a prosecutor, she told him, could give him experience she couldn’t. Against his instincts, he agreed to apply and sit for an interview with former Sussex Commonwealth’s Attorney Vincent Robertson, who despite Dante’s lack of trial experience, offered him the job on the spot.

Dante’s first trial

Dante’s legal career has mirrored Gammiel’s in more ways than one. They both passed multiple bar exams on their first attempt, Poindexter having taken hers shortly after making history in 1968 as one of the first two Black women to graduate from Louisiana State University’s law school, four years after the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act.

They also both lost their first trials.

Dante recalls he’d been prosecuting an animal cruelty case, which by luck of the draw had been assigned to be heard by “one of my favorite judges.”

When Dante asked a witness on the stand whether he recognized the person seated at the defendant’s table, the witness responded, “I can’t really say,” and the case got dismissed. That day he learned the hard way to always interview witnesses beforehand.

“It was embarrassing,” Dante said.

“It happens,” Robertson and his chief deputy-turned-successor, Regina Sykes, told Dante after the trial. “You’re going to lose lots of times; you’re going to win lots of times.”

“They gave me the confidence to go stand in court and put on a case,” Dante said.

Gammiel Poindexter in 1987 when she ran for re-election as Surry commonwealth’s attorney (Smithfield Times archives photo)

Gammiel, who’d again made history in 1975 when she was elected as the state’s first Black female commonwealth’s attorney, saw her first case as a prosecutor two months later in January 1976.

“I’ll never forget the first court date,” she said.

That day, the Surry courthouse was packed full of supporters who’d helped carry Poindexter to her 11-vote victory over her white predecessor, John Baker, only to watch the judge throw out all of her cases.

“Not too many months after that I heard the judge make a racial epithet in court,” Gammiel recalls. “I made him correct himself.”

She went on to successfully prosecute two men charged with attempting to sabotage Surry’s nuclear power plant in the late 1970s.

“Ever since I was a little girl, 8 or 9 years old, I said I wanted to be a lawyer,” Gammiel said.

She met Gerald in 1971 at a legal conference in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, shortly after he too graduated law school, though, “he always told me he wanted to be a scientist,” Gammiel said. The couple married a year later. When Surry became one of the first three counties in the United States to elect a majority Black governing board, Gerald was appointed state’s first of Black county attorney and later was elected commonwealth’s attorney in Gammiel’s place when she was appointed to the bench.

Surry, since 1972, “has been a place where Black people are given a place, equal opportunity, to serve,” Gammiel said. “I think they’ve done well.”

In mid-2023, Dante again approached Gammiel about working together as law partners, and this time, she didn’t say no. By December the firm Poindexter & Wright opened its doors, specializing in criminal defense, personal injury and family law matters.

“I’m just thankful for God’s grace and guidance, and I look forward to advocating for the citizens of the Tidewater area,” Dante said.